Current events make the need for open education greater than ever, but there are fewer resources available to support this work. This series of posts considers three ways to change the frame on how advocates make the case for OER.

Publishing models: Adding information

To borrow a saying from statisticians: “All models are wrong, but some are useful” (attributed to George Box). One way that models are wrong is that they always have a frame around them – and the frame inevitably leaves out some information.

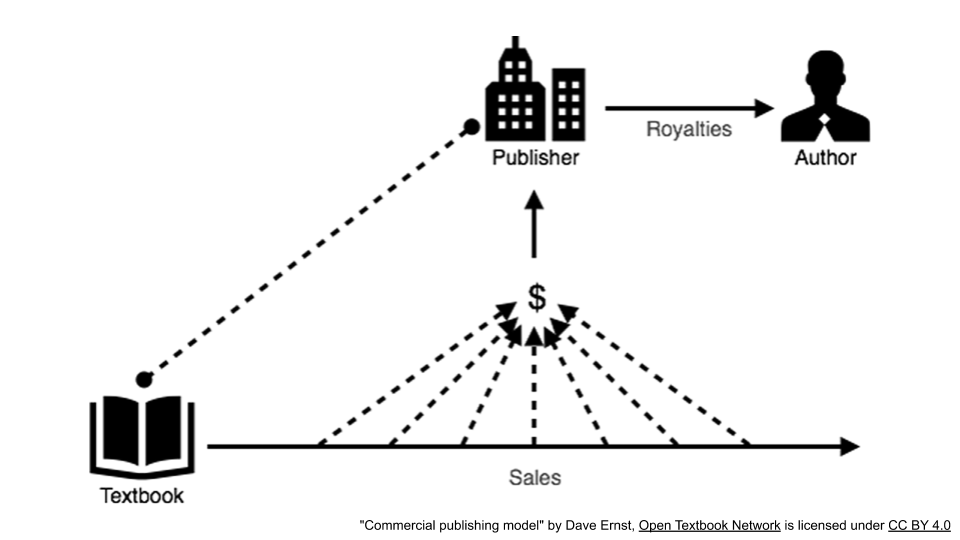

Dave Ernst’s OER Review Workshop slide deck includes a model of the commercial publishing process. The model shows that the publisher produces the all-rights-reserved textbook, which is sold to students in order to generate revenue through sales. Authors are paid royalties out of the revenue.

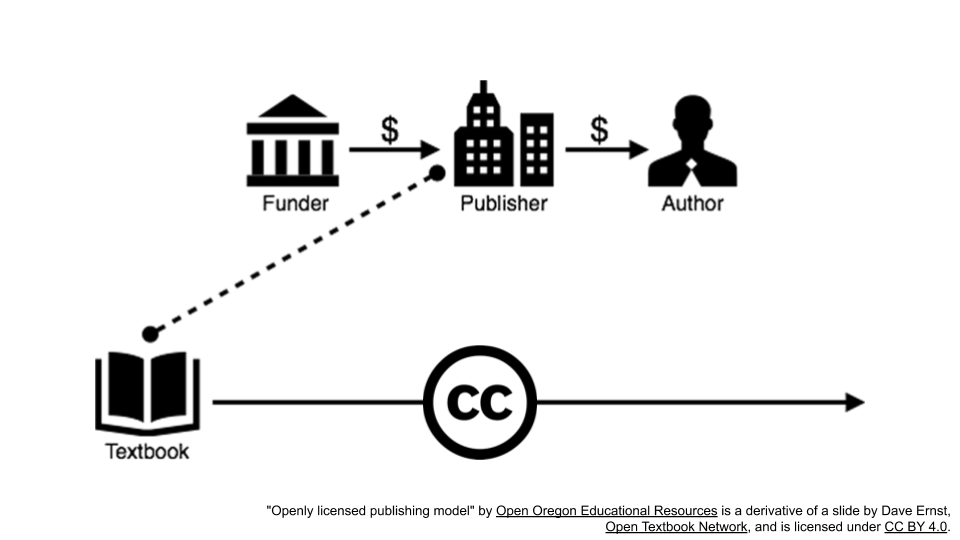

This model sets up a contrast with the publishing process for openly licensed textbooks. A funder provides money to the publisher in order to produce the textbook and pay a flat fee to the author, and the book is distributed online for free or in print at low cost.

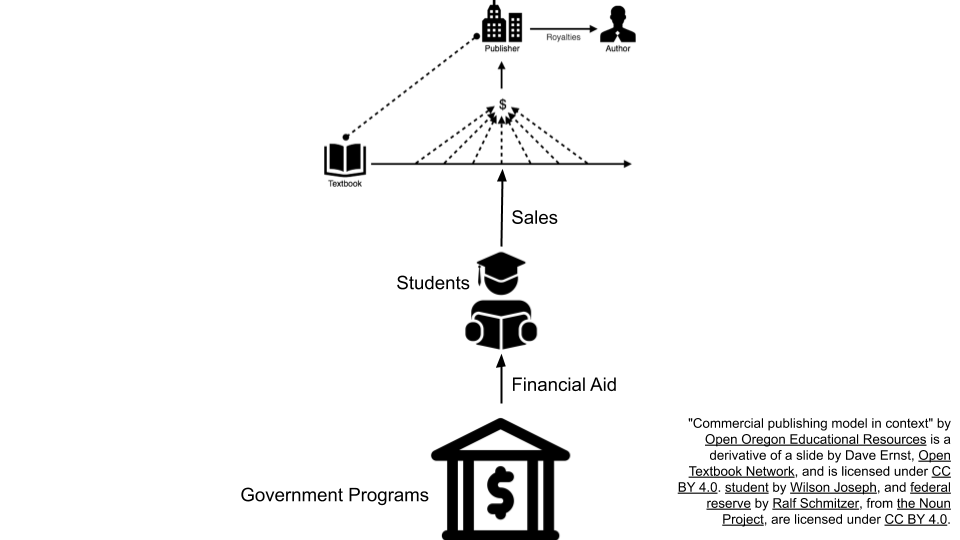

Coming back to the commercial publishing model, though, what if we pull back the frame? Doing so adds important information that changes the narrative. Students are likely to make textbook purchases with publicly funded financial aid dollars, whether loans or grants. The U.S. Public Interest Research Group estimated in 2016 that one-third of students use financial aid to pay for textbooks and argues that “alleviating high textbook costs could free $3.15 billion in state, federal, and local funding for use in reducing other higher education costs” (Covering the Cost: Why We Can No Longer Afford to Ignore High Textbook Prices). The model below adds those elements into the frame.

Pulling back the frame shows why affordable textbooks meet the moment. Students are facing new hardships at the same time that the federal, state, and local governments are stretched thin because of the pandemic. Both students and governments are stakeholders with urgent needs that could be addressed by redirecting the spending that currently goes towards textbook purchases.

Are there other examples where changing the frame enables us to shift the conversation about open education? Please leave a comment!

I love how this image and description illustrate the importance of how we use public funds! I’m going to have to think about how to adapt it to describe K-12 instructional materials purchases.

Hi Vanessa, I’ll be very curious to see that adaptation – please share! I passed by a related post on Twitter yesterday from Steven Bell at Temple University, reacting to a news article on students spending their $600 stimulus checks on textbooks: https://twitter.com/blendedlib/status/1341500842411765770 – Amy