This post was contributed by Tamara Marnell, ILS & Discovery Librarian, Central Oregon Community College. Thank you Jennryn Wetzler, Assistant Director of Open Education, Creative Commons, for a careful read and feedback. Disclaimer: Tamara Marnell is not a lawyer. This blog post is not legal advice. Consult an IP attorney for specific questions about copyright.

Revising and remixing OER is simple…in theory. An instructor planning a course finds the perfect openly licensed materials, sews them together tidily, and shares the adaptation with students who save a million dollars while the sun shines and fuzzy bunnies frolic under rainbows. Easy peasy!

In reality, an OER project is rarely easy peasy. An instructor putting together a new text will probably find many sources with different open licenses, some incompatible with others. “Free” educational materials they find online might have no licenses at all. Then what?

What are the licenses?

The first and most important step in remixing sources into a new published work is to figure out (a) who owns the copyright and (b) what permissions those copyright holders give to downstream users. If the copyright holders applied a Creative Commons or other clearly defined open license, this step is simple.

Unfortunately some content creators who intend to share their work openly simply post it online with no explicit licensing. A university department might link to worksheets for students and label them “free to download.” A subject expert might create a website with a single sentence on the About page that says their content is “open-source,” but with no specifics addressing the 5 Rs.

In these cases, we must assume the work is “all rights reserved” and ask for permission before using it in an OER project. The only way to be certain of the creators’ intentions is to ask.

Which licenses are compatible?

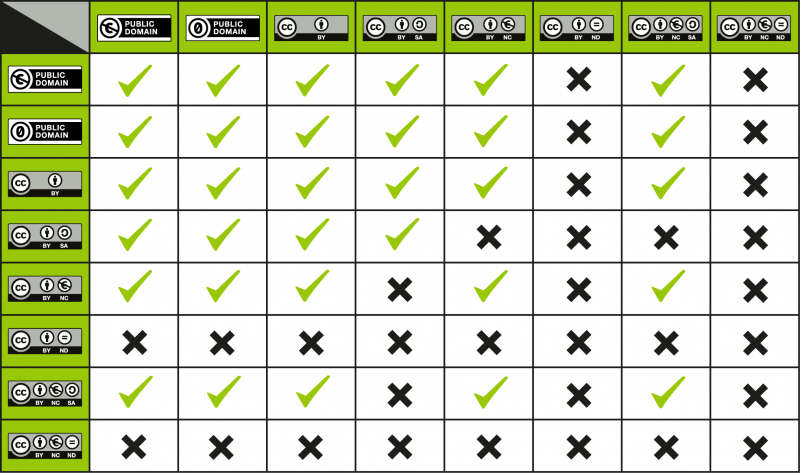

Once you identify the licenses, you have to figure out if they’re compatible with each other. In particular, the No Derivatives (ND) and Share Alike (SA) building blocks of CC licenses create conflicts with other licenses.

Works with an ND license can’t be remixed with any other works. The licenses will state, “If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you may not distribute the modified material.”

Works with SA licenses can’t be remixed with different licenses that impose more or fewer restrictions. These licenses will state, “If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you must distribute your contributions under the same license as the original.”

For example, CC BY-SA and CC BY-NC-SA are inherently incompatible. Both licenses require all derivatives to use the same license as the original, with no fewer or additional downstream restrictions. The Creative Commons Wiki explains further on the page “Wiki/cc license compatability.”

It is not possible to mix works where the first work is placed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike license and the second work is licensed under a Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike license. The ShareAlike building block in first license requires that the newly created work is released under that license and can therefore be used commercially, the second license wants you to release the new work under a license that does not permit commercial use.

The wiki page also contains this handy chart for reference.

This image, “License Compatability Chart” by CC Wiki, is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 license.

What can you do if sources are incompatible?

1. Make a “collection.”

If instructors want to combine materials from incompatible sources with no modifications, they can put together a “collection” that is not a derivative. In a collection, differently licensed materials are kept distinct and clearly attributed. This enables downstream users to recognize the differently licensed materials within the work and still abide by the materials’ respective permissions.

The Creative Commons Certificate course defines the difference between a derivative adaptation/remix and a collection in Unit 4.4: Remixing CC-Licensed Work. The lesson makes this analogy:

- Like a smoothie, an adaptation / remix mixes material from different sources to create a wholly new creation…In a “smoothie” or adaptation / remix, you often cannot tell where one open work ends and another one begins.

- Like a TV dinner, a collection compiles different works together while keeping them organized as distinct separate objects. An example of a collection would be a book that compiles openly licensed essays from different sources.

Jennryn Wetzler, Assistant Director of Open Education for Creative Commons, clarifies, “While this isn’t a black and white issue, if someone merely aggregates standalone works together as-is, she is not likely creating an adaptation–she is creating a collection. Even making some aesthetic changes to the works, like adjusting formatting or adding images would not be considered an adaptation. If the person began making more meaningful changes to integrate the works together, then the resulting creation is more likely to be a remix.”

2. Link out or embed.

You can link to or embed any website, streaming video, or file in an OER regardless of the license on it. As long as the content lives in its proper place and you abide by the license permissions of the material you’re using, you can point to it without infringing on copyright.

For example, if an educational video has a Standard YouTube license and the creator allows embedding, you can use the script provided under “Share” to place the video within an openly licensed lesson. You can’t download the video and redistribute the file, but as long as it stays on YouTube, you can incorporate it into your material.

Using linked or embedded content comes with risks. The original creators can delete their online articles or YouTube videos at any time. Links out frequently break when URLs change or domains expire. If you link to external content, you should check those sources regularly and be prepared to replace them with other sources if necessary.

3. Adjust the scope of the project.

If an instructor’s main goal is to provide resources for students, not to publish and share widely, scaling down the project can get around some compatibility issues.

For example, an instructor who wants to use selections from texts with incompatible CC licenses could revise and share them individually as distinct readings (providing the licenses allow revisions). Or the instructor could combine selections in Learning Management System (LMS) modules and make a fair use argument instead of using them under the terms of the conflicting open licenses. Portland Community College’s Guide to Fair Use can help you determine whether your planned use of the materials will qualify.

However, posting materials exclusively in an LMS, or creating multiple small readings, shifts the burden of printing to students. Making one complete and bound OER title available at the school bookstore allows students to use financial aid awards to purchase their materials.

4. Ask permission.

If only one or two sources are incompatible with the others, you can reach out to the authors of those works and ask for permission to use them in this project. For example, you can explain you’re using multiple books with CC-BY-NC-SA licenses, so you must use the same license on your final product, but you’d like to incorporate this worksheet from their CC-BY-SA text.

5. Find or create an alternative resource.

You can avoid the headache of incompatibility by finding other sources with less restrictive licenses. CC-BY is ideal.

You can also make your own sources. How unique is that exact CC-BY-SA worksheet? Don’t plagiarize, but you can apply your own knowledge to create a new work and license it however you please.