This post was contributed by Kevin Moore, Reference Specialist, Mt Hood Community College.

One of the great advantages of using OER is the freedom to choose high-quality materials and recombine them for your own instructional purposes. So long as you properly attribute sources licensed to share and edit, you can publish and distribute these remixes to your students.

But wait. How do you properly attribute sources that have been remixed, mingled, and mashed up?

This guide will help you attribute remixed materials following attribution standards established by Creative Commons, while maintaining readability and usability for your students. It will also consider accessibility issues for students who require screen readers. For more detail on creating accessible OER, visit the BC Open Textbook Accessibility Toolkit.

Basic Attribution Statements

The first step is to create proper attribution statements for the individual items you are going to remix. The easiest way to do this is with the very handy Open Attribution Builder created by the great folks at Open Washington. For more detail on writing attributions, consult the Attributions tab of the MHCC Textbook Affordability Libguide or Creative Commons Best practices for attribution.

Digital OER

The most common type of OER is published and distributed on the Internet in digital formats. This includes web sites, web pages, PDFs, online tools, videos, etc. As such, the attribution for a digital OER is the most common type of attribution you will find and makes a good introduction to creating attributions. It contains four essential elements: title of the work, author/creator statement, source or link to the original work, and license.

Below is an attribution made with the Open Attribution Builder. Here I used the tool to create an attribution for the tool itself. (Very “meta”, eh?)

“Open Attribution Builder” by Open Washington is licensed under CC BY 4.0

Note that the title, author/creator and license included links to their respective sites. Most OER appears on the Web or in digital formats with hyperlinking functions, so most likely you will share these resources with your students in the same way.

Print OER

If you are publishing OER materials in print formats (books, posters, etc.), you will need to remove the hyperlinked text. However, it is good practice to spell out the link to the original source, as in this example:

“Open Attribution Builder” by Open Washington is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Available at http://www.openwa.org/attrib-builder/

Attributions for Multiple Sources

Once you start combining OER, properly attributing multiple sources can raise questions.

For example, let’s look at a typical Philosophy 101 topic: Socrates. I’ve combined biographical information from an open Philosophy 101 lecture with some openly licensed critical commentary from Wikipedia, followed by appropriate open license attributions.

Socrates (ca. 469 – 399 B.C.E.) (Greek Σωκράτης Sōkrátēs) was an ancient Greek philosopher and one of the pillars of the Western tradition. Having left behind no writings of his own, he is known mainly through Plato, one of his students. Plato used the life of his teacher and the Socratic method of inquiry to advance a philosophy of idealism that would come to influence later Christian thought and the development of Western civilization.

“Socrates” by New World Encyclopedia is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

Some modern scholarship holds that, with so much of his own thought obscured and possibly altered by Plato, it is impossible to gain a clear picture of Socrates amid all the contradictory evidence. Some controversy also exists about Socrates’ attitude towards homosexuality and as to whether or not he believed in the Olympian gods, was monotheistic, or held some other religious viewpoint. However, it is still commonly taught and held with little exception that Socrates is the progenitor of subsequent Western philosophy, to the point that philosophers before him are referred to as pre-Socratic.

“Socrates” by Wikipedia is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

In this example, the two passages work well together. However, their attribution statements break the flow of reading. For students who require the assistance of screen reading devices, these attribution statements can be even more disruptive. A typical screen reader reads aloud everything written on the page, and reads the visual descriptions and captions for media such as embedded videos and images. As you can imagine, hearing a robotic voice read aloud attribution statements immediately after every source in a remixed OER would be monotonous, distracting and probably a little irritating.

There isn’t a single way to solve this problem, but I’ll make some suggestions.

Note that not all instructors using multiple sources to create OER will need to remix them. It may be easier to provide links to videos, chapters of online texts, and so on, than to recombine these elements. However, instructors who seek to “mash up” several sources will want to consider different ways to attribute multiple sources individually that can be used to attribute remixed OER.

Link List with Terms of Use Statement

One best practice for attributing multiple sources is to list links to each source in an attribution section at the bottom of the page that the content appears on. The example below is how an open composition course provided by Lumen Learning attributes all the sources that were used on one page of a module.

LICENSES AND ATTRIBUTIONS

CC LICENSED CONTENT, ORIGINAL

- Revision and Adaptation. Provided by: Lumen Learning. License: CC BY: Attribution

CC LICENSED CONTENT, SHARED PREVIOUSLY

- PQRST Script. Provided by: Lethbridge College. Located at: http://www.lethbridgecollege.net/elearningcafe/index.php/pqrst-script. Project: eLearning Cafe. License: CC BY: Attribution

PUBLIC DOMAIN CONTENT

- How to Write an A-plus Summary of a Text. Authored by: Owen M. Williamson. Provided by: The University of Texas at El Paso. Located at: http://utminers.utep.edu/omwilliamson/engl0310/summaryhints.htm. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

“Licenses and Attributions” from Developmental English: Introduction to College Composition, by Lumen Learning is licensed under CC BY 4.0

Put it in the Syllabus

If your remixed OER makes significant use of a few resources, it’s a good idea to make note of it upfront in the course syllabus. This should not be your only attribution statement, but it will make it clear to the reader where the original source material is from. The Philosophy 101 course syllabus at Saylor Academy provides an excellent example, excerpted below.

Course Information

Welcome to Philosophy 101. Below, please find general information on this course and its requirements.

Course Designers: Nikolaus Fogle, Ph.D., Renmin University of China and Chad Redwing, Ph.D., University of Chicago

Primary Resources: This course is composed of a wide range of free online materials. However, the following course content relies heavily on the following sources:

- iTunes U: Dr. Nigel Warburton’s Philosophy: The Classics

- Yale University’s Open Yale Courses: Dr. Steven B. Smith’s “Introduction to Political Philosophy,” Professor Iván Szelényi’s “Foundations of Modern Social Theory,” and Professor Ian Shapiro’s “The Moral Foundations of Politics”

- Stanford University’s Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- The University of Tennessee at Martin’s Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

Course Syllabus for “PHIL101: Introduction to Philosophy” by Saylor Academy is licensed under CC BY 3.0

Attributions in the Body of Remixed OER

In both of the above examples, the attributions appear separately from the body of the work itself. In this section I’ll talk about how you can properly attribute sources in a remixed OER by using either standard citation formats, or standard notation. I should emphasize here that using OER in academia is still in its infancy, and so far official, standardized guidelines have not been established to handle attributions for remixed content. This is precisely the reason I’m writing this document! I propose to use established sourcing methods in new ways to respect the intellectual work of OER creators in accordance with Creative Commons License practice.

Use Standard Citation Formats

Scholars make attribution statements through standard citation formats such as Modern Language Association (MLA 8) and American Psychological Association (APA) styles. Adapting this method to remixed OER can simplify the attribution process. By using the signal phrases used in scholarly citation, you can indicate a fuller attribution on a separate list of attributed works (traditionally known as a bibliography.)

For example, in the PHI 101 OER sample seen above, I can add a signal phrase:

Socrates (ca. 469 – 399 B.C.E.) (Greek Σωκράτης Sōkrátēs) was an ancient Greek philosopher and one of the pillars of the Western tradition. Having left behind no writings of his own, he is known mainly through Plato, one of his students. Plato used the life of his teacher and the Socratic method of inquiry to advance a philosophy of idealism that would come to influence later Christian thought and the development of Western civilization. (“Socrates”)

The signal phrase links to the original web page of the source. On the bibliography page, I could list the attribution statement after the citation.

“Socrates.” New World Encyclopedia, New World Encyclopedia, 8 Oct. 2015, www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Socrates. Accessed 16 Mar. 2017.

“Socrates” by New World Encyclopedia is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

However, this is pretty cluttered and redundant. It will be simpler to use only the signal phrase as a listing element, followed by the attribution statement.

“Socrates.” New World Encyclopedia, New World Encyclopedia, 8 Oct. 2015. Accessed 16 Mar. 2017. Licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

As you can see, I have mashed up MLA 8 citation with Creative Commons attribution to create something simpler, clearer, and respectful of CC licensing – as long as the bibliography stays with the work. As mentioned at the start of this section, this method is not common practice, but a proposed “work-around.”

As noted earlier, screen readers read everything that is on the screen, so it is important to choose carefully how much information to provide it to read. The work-around I have created here might make listening to the screen reader annoying, as it announces every signal phrase, and could distract the student from learning. In that event, it might make more sense to use footnotes (provided a screen reader is set to read them), as described in the next section.

Use Footnotes (or Endnotes)

Another time-tested approach scholars have used is citing sources with footnotes (or endnotes, if you prefer). With OER you don’t have to worry about adhering to strict rules in, say, The Chicago Manual of Style. But in this example I will rely upon the Notes And Bibliography (NB) system for coherence and consistency. The NB system has been used traditionally to protect authors from plagiarism; for OER, we can use this system to respect the CC licenses of OER originators.

Here is the Socrates example again, using the NB System.

Socrates (ca. 469 – 399 B.C.E.) (Greek Σωκράτης Sōkrátēs) was an ancient Greek philosopher and one of the pillars of the Western tradition.1

1“Socrates” by New World Encyclopedia is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

Using superscripts may be the simplest and clearest way to incorporate attribution statements in remixed OER.

So far I have discussed text-based OER. In the following section I will look at how attributions can work in visual media, such as videos and images.

Attributions in Remixed OER in Visual Media

Images present intellectual property challenges. The Internet abounds in images that users have appropriated with little or no regard for their original creators (photographers, illustrators, cartoonists, etc.), stripping image credits and copyright notices from the original image file before altering and reposting. This can make it difficult to determine the original creator of an image you want to use. Similar problems arise with trademarked images (think Grumpy Cat) and likenesses (Kim Kardashian West).

In the U.S., the debate over the power of copyright to limit freedom of expression (or vice-versa) is long, deep, and thorny. In most cases, artists and educators are protected by Fair Use exceptions that allow for creativity, teaching, and significant modification. Parsing those cases is beyond the scope of this discussion, but I recommend consulting your college librarian to determine how best to legally incorporate visual content under Fair Use. Generally speaking, unless you see an open license, you should assume that content on the internet is under copyright.

Many open source images fall in the public domain, where all things past their copyright expiration date go to pasture. This means Monet’s water lily paintings are yours to do with what you see fit. Yet there are good reasons to attribute an open source image. It is good scholarly communication practice (citing sources for readers to find on their own). It enables you to find the source yourself later, if you need to. And while Claude Monet has long ceased to exist, many creators of open source images are still thriving and have generously provided their work to the public to use. They deserve credit for their work.

Let’s take a look at attributing sources in different visual media.

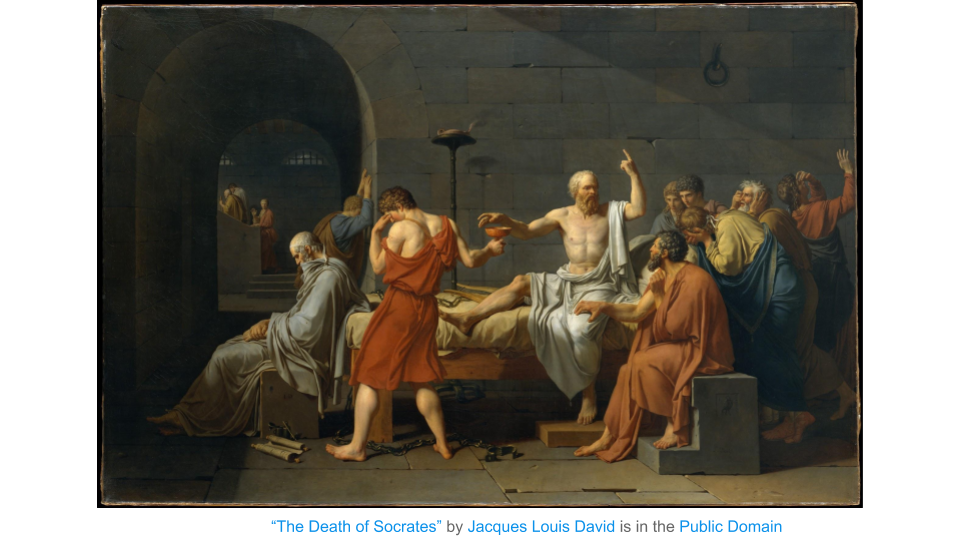

Images

Captions remain a reliable way to provide the creators or owners of an image proper credit, while also using CC license attributions. Some word-processing and web design software will enable you to create a caption that is attached to the metadata for the image, which helps users of screen readers. The caption on the image below provides an example.

“The Death of Socrates” by Jacques Louis David is in the Public Domain

Slide Presentations

Presentation software such as PowerPoint provide instructors with creative ways to remix open resources and attribute those sources. Below see two slides using the Socrates example. In the first slide, the caption provides the attribution for the image, much as it would in a text-based document. On the second slide, I have taken only the essential information from the New World Encyclopedia entry and put it in bullet points. Nonetheless, I have given proper credit using the same attribution statement I created with the Open Washington attribution builder.

Online Videos

Videos are a great way to provide lectures to students, and with the ability to directly export a PowerPoint Presentation to YouTube, a very easy way, too. Indeed, the slide presentation example above demonstrates a simple method of putting attribution statements into videos using remixed OER. If I were to turn my Socrates slide presentation into a video, the attribution statements are already included.

Another method is to put the attribution statement at the end of the video. In the video Science Commons by Creative Commons, at the 1:52 mark a slide states that “All images and music used to create this work were licensed under Creative Common licenses.” Credit slides then list the originators alphabetically.

When you upload a video to YouTube, you have the option of selecting the license type, one of which is a Creative Commons license. For good examples of this practice, take a look at the videos on the Open Oregon channel on YouTube. You can find the license statement in the “about” box under the video.

Conclusion

Creating new OER by taking relevant pieces of content from several openly licensed sources and remixing them into a coherent whole is a great way to make affordable learning tools available to your students that resemble more closely your own pedagogy, as opposed to using a single OER source, or a traditional textbook where publishers make these pedagogical decisions for you and overcharge your students for it. However, the task of remixing relevant OER resources into a single teaching material is complicated by the fact that OER sources can have different types of open licenses. Therefore, it is very important to keep track of the different Creative Commons licenses your original sources use in order to simplify the process of creating attribution statements for your remixed learning tools. For help in this area, consult the CC License Compatibility Chart.

Besides accounting for and abiding by all the different licenses used for your remixed learning tool, one has to keep in mind accessibility issues, specifically, how the placement of attributions within your remixed learning tool can affect the students’ experience using it. The presence of hyperlinks, non-friendly URL’s, and other non-syntactic text within your teaching materials’ content can affect the overall user experience, especially when the student uses accessibility tools like screen readers. It is for this reason that I recommend listing attribution statements in places other than within the body of your learning tool’s content. Attribution statements can be included at the end of the document, linked to outside the learning tool in the syllabus, as an MLA or APA-style works cited or bibliography, or as footnotes or endnotes. Following the recommendations above will ensure your students will have an accessible and affordable learning tool that properly attributes and credits each of the sources contributing to your remixed OER.

References and Further Reading

“Best Practices for Attribution.” Creative Commons Wiki. Creative Commons, n.d. Web. 12 Aug. 2016. <https://wiki.creativecommons.org/wiki/Best_practices_for_attribution>.

“Foter Blog.” Foter Blog. Foter.com, 4 Mar. 2015. Web. 12 Aug. 2016. <http://foter.com/blog/how-to-attribute-creative-commons-photos/>.

“Marking Works Technical.” Creative Commons Wiki. Creative Commons, 25 Sept. 2014. Web. 12 Aug. 2016. <https://wiki.creativecommons.org/wiki/Marking_Works_Technical>.

Pingback: City Tech’s OpenLab Pedagogy Event, Thursday October 18th | LitHub@Hunter