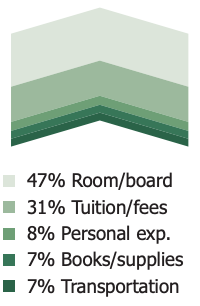

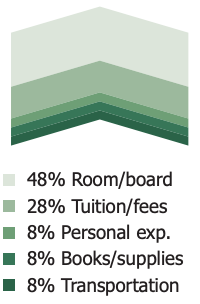

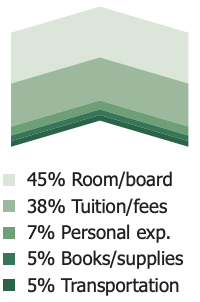

The cost of textbooks is a small dollar amount compared to the total cost of attendance. In Oregon, data from the Higher Education Coordinating Commission shows that statewide, the biggest slice of the pie goes to housing, and tuition is a close second. Books and supplies on average are 7% of the $19,952 total cost of attendance, or about $1400.

|

Statewide public postsecondary cost of attendance components |

Does it really make sense to worry about a cost that, relatively speaking, is small compared to the total cost of attendance? Short answer: yes. Here are three reasons why seemingly small dollar amounts are significant. Taken together, they confirm that lowering textbook prices makes a big difference for students and that support for faculty to use open educational resources is an effective use of public funding.

1. Small dollar amounts can be an emergency

We know from the work of researchers such as Sara Goldrick-Rab that financial aid does not cover the cost of higher education. This is true in both colleges and universities, though community college students may be more likely to face food and housing insecurity: a study by Sara Goldrick-Rab, Jed Richardson, and Anthony Hernandez for the Wisconsin HOPE Lab “found that two in three students are food insecure… about half of community college students were housing insecure, and 13 to 14 percent were homeless” (p. 1).

Even after making a commitment to higher education that includes taking out loans, the kinds of financial emergencies that cause students to drop out may not have high price tags. In fact, according to the National Association of Student Personnel Administrators (NASPA), emergency aid is defined as assistance to meet a need of less than $1500:

Emergency aid includes one-time grants, loans, and completion scholarships of less than $1,500 provided to students facing unexpected financial crisis, as well as food pantries, housing assistance, and transportation assistance. (Landscape Analysis of Emergency Aid Programs, p. 25)

In their national survey of over 700 institutions, NASPA found that most emergency aid, in the form of campus vouchers, emergency loans, and unrestricted grants, is likely to be for dollar amounts of $100-$500. This is the model adopted by Goldrick-Rab’s FAST Fund nonprofit, which enables faculty to directly give students financial assistance to help them stay in school. Because, of course, if a student has to drop out, they still have to pay back those student loans – but without the degree that confers higher earning power.

That statewide average of $1400 for books and supplies is a potential emergency for students who don’t have a financial cushion. As PhD candidate Amy Nusbaum wrote regarding a student who couldn’t afford $65 for the textbooks she needed:

I often hear faculty saying that full open access isn’t possible. That their textbooks are “only” $70, so it’s not a burden. And, yeah, sure $70 is better than $150 is better than $300. But if we continue to think “oh, it’s just $65,” we will continue to have students like this one being disadvantaged. Scraping by. Choosing between food and books. Dropping out. So, what’s the take-away? Stop assuming that X amount of money that’s doable for you won’t be a barrier for your students. Because unless that amount is $0, it will be a barrier for someone.

2. Faculty have a direct impact on course materials costs

It’s very difficult to change the upward trend of tuition costs, and arguably even harder to budge the cost of housing in your community. The cost of course materials is significant and it’s the one component of the total cost of attendance that faculty can directly control. Faculty choices have a big financial impact on students.

Bookstore managers use a number of strategies to help keep costs down, including bundles, inclusive access, custom editions, older editions, and rental programs. Faculty and librarians have also pursued strategies such as a single purchase for multi-term sequence, using free content from the web, and assigning library resources as course materials. Students, of course, develop their own strategies to cope with costs: buyback, book swaps, international editions, sharing, library reserves, and comparison shopping. All of these strategies are important because every dollar counts.

Open educational resources are different from all of these strategies, because they solve the root cause of the cost problem by using open licenses in addition to traditional copyright. Faculty can download the material, tailor it to their learning outcomes, and share it back out with attribution, all without violating copyright. This gives faculty more control over the quality of their course materials than with a traditional publisher textbook. The open license gives permission to redistribute for free online or in print at low cost.

With copyrighted content, the publisher can always raise the cost of access; even free content available online can suddenly disappear or move behind a paywall. Openly licensed content can be saved locally and shared widely, taking away dependence on third parties; students can save their own copy for lifetime access, which is the opposite of the rental model.

Faculty who want to take action to make higher education more accessible to students can redesign their courses using open or affordable materials. In departments where course materials decisions are made collectively, it may take longer to reach a group decision but the impact will be greater.

3. This is an effective use of funding

Changing your course materials is a lot of work. Faculty need support in order to do this work. Funding for course redesign using open and affordable course materials is an effective use of institutional and legislative dollars because it makes higher education more accessible for students.

Supporting course redesign to lower costs has a multiplier effect on student savings. Open Oregon Educational Resources data from the 2016-17 grant program shows that every program dollar spent resulted in approximately $4 in student savings during the pilot. Followup data from the 2015 grant program shows that one year after the pilot ended, student savings had approximately tripled from the initially reported amount. Savings will continue to compound as more students enroll in the redesigned courses and more faculty convince their colleagues to adopt their redesigned courses.

Compared with other ways to spend public funds to lower the cost of attendance, support for course redesign is effective and high-impact.

Takeaways

- Seemingly small dollar amounts are significant – in fact, they can create an emergency that results in students dropping out in spite of their loan obligations.

- Faculty have a direct impact on course materials costs and can help solve the root cause of the cost problem by adopting open educational resources instead of commercial textbooks.

- Supporting faculty adoption of open educational resources is an effective use of institutional and legislative funds.